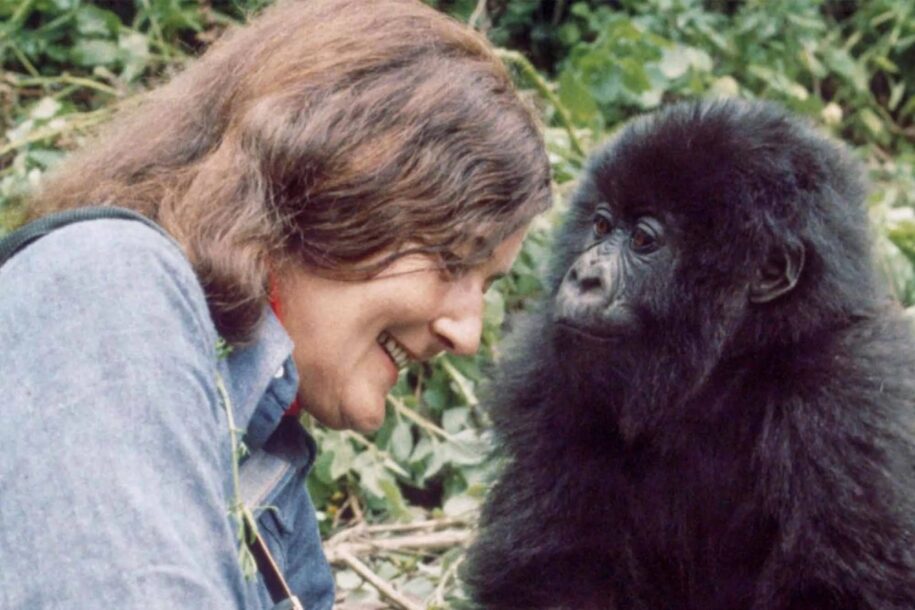

Dian Fossey remains one of the most consequential figures in the history of wildlife conservation in Africa.

Her pioneering work in Rwanda’s Virunga Mountains, beginning in 1967, created the foundation upon which modern gorilla research and tourism were built.

Trained as a primatologist, she combined field discipline with a conservationist’s urgency at a time when mountain gorillas faced severe population decline. Her methods and findings continue to inform ecological management frameworks applied within Volcanoes National Park today.

Fossey’s decision to establish the Karisoke Research Center between Mount Karisimbi and Mount Bisoke marked the beginning of long-term behavioral observation of mountain gorillas in their natural habitat.

Besides documenting their social dynamics, she identified key threats such as poaching and habitat encroachment, shaping future conservation policy. Her detailed journals and publications attracted global attention to Rwanda’s gorillas, helping transform them from a threatened species into a cornerstone of national identity and sustainable tourism.

Dian Fossey’s work influenced Rwanda’s later integration of conservation into its tourism economy.

The principles she advanced became operational pillars for gorilla trekking programs introduced decades after she died in 1985. These programs today sustain both ecological preservation and local livelihoods through structured visitor access and revenue-sharing models.

As you explore her story, observe how Fossey’s scientific rigor, though rooted in protection, inadvertently enabled the development of a globally respected tourism model.

Her legacy remains inseparable from Rwanda’s transformation into a destination defined by responsible wildlife stewardship and conservation-based tourism.

Who Was Dian Fossey?

Dian Fossey was born in San Francisco, California, in 1932. She pursued pre-veterinary studies before earning a bachelor’s degree in occupational therapy from San Jose State College in 1954. Her interest in Africa was inspired during a self-funded trip in 1963, where she first encountered mountain gorillas during a guided excursion in the Congo.

In 1966, with encouragement from renowned anthropologist Louis Leakey, Fossey committed to long-term primate field research. The following year, she returned to central Africa and established the Karisoke Research Center in the Virunga Mountains of Rwanda.

Its location—between Mount Karisimbi and Mount Bisoke—was selected for proximity to key gorilla groups and relative isolation from poaching routes.

At Karisoke, Fossey implemented daily observation protocols, recording gorilla behaviors, group hierarchies, dietary patterns, and vocalisations. Her approach combined scientific discipline with an unusual level of immersion. Over time, she succeeded in habituating several gorilla groups to human presence without disrupting their social structures.

Besides her research, Fossey maintained extensive correspondence with international institutions, including the National Geographic Society. Through published articles and media coverage, she gained support for continued field operations and highlighted the existential threats facing the species.

By 1980, her findings had redefined global understanding of Gorilla beringei beringei, the mountain gorilla subspecies native to the Virunga massif.

Her work later culminated in the book Gorillas in the Mist, published in 1983. The book provided the public with the most comprehensive insight into gorilla ecology at the time.

The Conservation Fight: Protecting Rwanda’s Mountain Gorillas

By the late 1960s, Rwanda’s mountain gorillas faced existential risks. Their population had declined significantly due to poaching, illegal wildlife trade, and agricultural encroachment.

Dian Fossey, based at Karisoke, documented the extent of these threats with methodical precision. She identified wire snares, firearm injuries, and habitat fragmentation as immediate dangers to the survival of gorilla groups under observation.

In addition to data collection, Fossey took direct action. She organised anti-poaching patrols composed of local trackers and research assistants. These patrols located and dismantled snares, traced poacher movement, and reported evidence to park authorities. She also documented poaching incidents in her research logs, contributing to pressure on local enforcement agencies to respond.

The death of Digit, a silverback gorilla, in 1977 marked a turning point in her conservation strategy. Killed by poachers, Digit had been one of the first gorillas to be fully habituated at Karisoke. Fossey responded by founding the Digit Fund (now the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund) to raise international support for anti-poaching interventions. This initiative laid the groundwork for externally funded conservation partnerships in the region.

Fossey also opposed any form of gorilla commodification. She criticised wildlife trafficking, trophy hunting, and unregulated tourism as threats disguised as opportunity. Her stance, though unpopular in some circles, established an ethical baseline for later conservation-tourism models in Rwanda.

The Turning Point: How Dian Fossey Inspired Gorilla Tourism

Dian Fossey maintained a firm opposition to mass tourism throughout her career.

Her field notes repeatedly expressed concern over gorilla stress, disease transmission, and behavioral disruption. However, her work at Karisoke inadvertently created the enabling environment for what would become one of Africa’s most controlled and conservation-driven tourism models.

Through her detailed publications and international lectures, Fossey made mountain gorillas visible to the global public.

The release of Gorillas in the Mist in 1983 and the subsequent film adaptation in 1988 amplified that visibility. Interest in Rwanda’s gorillas increased among policymakers, conservation donors, and structured tourism operators.

In the early 1990s, the Rwandan government, in partnership with conservation NGOs, began developing a formal gorilla trekking program within Volcanoes National Park.

This program borrowed directly from Fossey’s habituation protocols, which allowed selected gorilla groups to tolerate limited human presence. Daily monitoring, strict visitor limits, and health precautions were all grounded in procedures first tested at Karisoke.

The scientific data from Fossey’s studies helped determine which gorilla families were eligible for habituation and what minimum distance should be enforced between humans and primates. These parameters became policy benchmarks for park authorities and tour operators.

You might find it surprising that someone so publicly opposed to tourism would become central to its operational logic. Yet, Fossey’s methods, especially her emphasis on observational integrity and low-impact human interaction, gave Rwanda a template for balancing ecological integrity with tourism revenue.

Legacy and Impact on Rwanda’s Tourism Economy

Gorilla tourism has become one of Rwanda’s highest foreign exchange earners, contributing over USD 150 million annually as of 2023. While Dian Fossey did not directly design this industry, her conservation principles formed its ethical and operational backbone. Rwanda’s strategy of limiting visitor numbers, applying high permit fees, and enforcing strict wildlife interaction rules emerged from her research protocols.

In 2005, Rwanda introduced the Tourism Revenue Sharing Scheme. This policy allocates 10 percent of all national park income to surrounding communities. The model was intended to reduce human-wildlife conflict by giving residents a direct stake in conservation. Karisoke’s early community outreach programs, although modest, set a precedent for these later frameworks.

Besides economic returns, gorilla tourism has supported major infrastructure upgrades. Roads, accommodation facilities, health clinics, and schools have been constructed in Musanze and adjacent sectors using tourism-linked revenue. These investments have elevated both the conservation value of the park and its social acceptability among local populations.

The presence of institutions like the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International and the Rwanda Development Board (RDB) has ensured continuous data-driven policy refinement. Both bodies reference Fossey’s methods in their guidelines for ranger training, veterinary intervention, and gorilla group monitoring.

Honoring Dian Fossey Today

Dian Fossey is buried at her original research site within Volcanoes National Park. Her grave lies beside Digit, the silverback gorilla killed by poachers in 1977. The site is accessible by foot, with a trail beginning near the park headquarters in Kinigi. Managed under the authority of the Rwanda Development Board, the site receives guided visits from researchers, conservation partners, and a limited number of tourists.

The Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International continues to operate in her name. It manages long-term gorilla monitoring, biodiversity research, veterinary interventions, and education programs across Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. As of 2022, its operations are based at the Ellen DeGeneres Campus, located near Musanze. The campus includes laboratories, classrooms, and a public conservation gallery.

Besides, Rwanda celebrates Kwita Izina, an annual gorilla naming ceremony, each September. Although not established by Fossey, the event aligns with her vision of humanising gorilla conservation through education and structured visibility. The event brings together policymakers, scientists, donors, and park staff to name newly born gorillas, reinforcing species monitoring and public engagement.

In addition, World Gorilla Day, observed every 24 September, commemorates Fossey’s work and highlights ongoing conservation priorities. If you’re planning to visit Rwanda for research or tourism, aligning your travel dates with this observance can provide deeper insight into the country’s conservation narrative.

Fossey’s influence, while historical, remains operational. Her name is preserved not only through tribute but also through continuous, science-based activities linked to Rwanda’s tourism and conservation sectors.

Conclusion

Dian Fossey was killed in her cabin at the Karisoke Research Center on 26 December 1985. The circumstances remain unresolved, but the impact of her work is neither ambiguous nor diminished. Her death halted a chapter in conservation science, yet it catalysed a global commitment to protecting mountain gorillas through formalised programs and policies.

Her legacy lives through data archives, community protocols, scientific institutions, and a national tourism model that aligns with ecological preservation. The controlled gorilla trekking framework in Rwanda, often praised for its balance between access and protection, draws its operational DNA from Fossey’s original research methods and field ethics.

Today, Volcanoes National Park welcomes thousands of international visitors annually. Each permit issued, each gorilla group monitored, and each conservation milestone achieved continues a trajectory Fossey helped establish. Rwanda’s tourism strategy benefits not only from global interest but from a credibility that began with one individual’s refusal to compromise the survival of a species.

As a reader with an interest in tourism policy or conservation strategy, consider how leadership grounded in field-based evidence can scale across generations. Fossey’s contribution did not end with publication. It transformed into infrastructure, policy, and cross-sector collaboration, defining Rwanda’s international tourism reputation.